IDA BELL WELLS - BARNETTJuly 16, 1882 � March 25, 1931

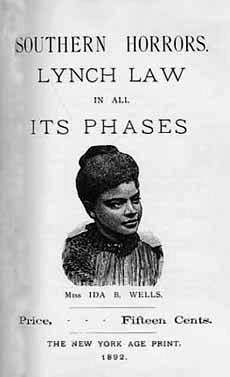

Journalist � Newspaper editor � Civil and Woman�s rights advocateIda B. Wells was born in Holly Springs Mississippi just before the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Both of her parents were born slaves and not freed until the signing of the Proclamation. Once her family gained their freedom Wells attended a school for freed people called Shaw University; it is now Rust College in Holly Springs. From the start of her life she would rebel against injustice. Her attitude earned her expulsion after an altercation with the principle of the school. Following her expulsion she went to visit her grandmother in the Mississippi Valley in 1878. It was while she was with her grandmother, Peggy Wells, that disaster struck her hometown of Holly Springs. She was notified that both of her parents had been killed when an epidemic of yellow fever struck. She was 16 years of age and had not only lost her parents but her youngest sibling, Stanley, as well. Stanley was only 10 months old. Against the advice of friends and relatives, who wanted the children to be taken to different foster homes, she decided to keep them together and be raised as a family. To support her family she had to drop out of Rust College and started to work as a teacher in a Black elementary school. With the help of her grandmother Peggy and other relatives she was able to make ends meet. These family members kept the children while she worked. She resented the disparity of pay for Black verses White teachers. White elementary teachers were paid $80 monthly while Black teachers were paid $30 a month. This discrimination added to her hatred of discrimination and injustice toward Blacks. She decided to involve herself in politics and the improvement of educations for Blacks. In 1883 she gathered three of her younger siblings and moved to Memphis, Tennessee to live with an aunt and to be closer to other family members. She found work teaching in the Shelby County school system where she earned more than she did in Mississippi. She attended summer sessions at Fisk University in Nashville. Ida had very strong political views on the rights of women and provoked many people with her forceful attitude. This was her hallmark and one that she would carry throughout her life. At age 24 she wrote:�I will not begin at this late day by doing what my soul abhors; sugaring men, weak deceitful creatures, with flattery to retain them as escorts or to gratify a revenge.� On May 4 1884 she was told by a train conductor on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad to give up her seat for a White passenger. She refused to do so and was dragged out of the car by the conductor and two white men. On her return to Memphis she wrote a blistering newspaper article titled: "The Living Way", a Black church weekly about the way she was treated on the train. She sued and won a judgment of $500. However on appeal the Supreme Court of Tennessee overturned the verdict. The court said: �We think it is evident that the purpose of the defendant in error was to harass with a vied to this suit, and that her persistence was not in good faith to obtain a comfortable seat for the short ride.� Wells was ordered to pay court cost. Wells continued her crusade against injustice in toward Black people with her writings. She soon became one of the most famous writers concerning injustice in the country. In the Spring of 1892 racial tensions were high in Memphis. Three of her friends, Henry Stewart, Calvin McDowell, and Thomas Moss owned the People�s Grocery Company. They started a co-op and began buying product cheaper by buying in bulk. Therefore they were able to sell product at a rate cheaper than that of some White stores. This led to a confrontation between their store and one of their White competitors. A White mob invaded the Black store and a fight broke out. Three White men were shot and injured. The Black owners were arrested and jailed. A lynch mob formed, raided the jail, drug the three men from their cells and lynched them. After the lynching of her friends Ida wrote a newspaper article urging Blacks to leave Memphis: �There is, therefore, only one thing left to do, save our money and leave a town which will not Protect or lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons.� Over 6,000 Blacks did leave and others organized boycotts of White owned businesses. These efforts brought Memphis to its economic knees and lynching of Blacks decreased dramatically. The murders also drove Wells to research and document lynchings and their causes. Her brutal finds were published in her book �Southern Horrors: Lynch Laws in All its Phases.� Threats to her life led to her leaving Memphis in favor of Chicago. Here she was to marry and raise four children. In spite of her marriage her staunch personality would not allow her to completely abandon her name. She was only a few of the millions of women in the country to keep her maiden name. Wells worked with other Black leaders in various agendas. Frederick Douglass approved of her work. He wrote: "You have done your people and mine a service�What a revelation of existing conditions your writing has been to me.� Wells also worked with W.E.B. Du Bois. Their lives ran parallel courses. They both used their journalistic writing to condemn lynching. One difference is the story of why Well�s name did not appear on the origin list of NAACP founders. Du Bois implied that she had chosen not to be included. On the other hand, in her autobiography she complains that Du Bois deliberately excluded her from being on the list. Wells spent a considerable amount of time in Europe speaking on the evils of the lynchings of Black people. She was well received in England as well as Europe. Her heart warming reception in Europe left some in the United States at odds with she and the European press. It was in England that Ida and the secretary of the "Woman�s Christian Temperance Union" Frances Willard clashed. This was one of the most powerful women�s orgaizations in the country with a membership of over 200,000. Wells worked feverishly for this organazation but they did not reciprocate. Wells and the Europen press thought that Willard and her organazation should not only promote the rights of women but also denounce the evils of lynchings. Beyond providing lip service they did little else. In 1892 Wells published a pamphlet titled �Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its phases, and A Red Record" This was the most complete research on lynching to date. After examining many accounts of lynching based on alleged �rape of white women,� she concluded that Southerners concocted rape as an excuse to hide their true reason for lynchings: Black economic progress, that threatened White Southerners purse strings but also their ideas about Black inferiority. She wrote: �The lesson this teaches and which every Afro-American should ponder well, is that a Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give. When the white man who is always the aggressor knows he runs at great risk of biting the dust every time his Afro-American victim does, he will have greater respect for Afro-American life. The more the Afro-American yields and cringes and begs, the more he has to do so, the more he is insulted outraged and lynched.�

DEATHAfter leaving Europe Wells spent the next thirty years of her life in Chicago. There she worked on urban reform and raised her family. She also took the time to work on her autobiography. It was called �Crusade for Justice.� Unfortunately she didn�t live to complete it. She died of kidney failure.

Further study click on the following

Ida B. Wells: Crusade for JusticePatricia A. Schechter. "Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880-1930". University of North Carolina Press. http://www.ibiblio.org/uncpress/chapters/schechter_ida.html. Retrieved 2011-04-31.

|