MARCUS GARVEY

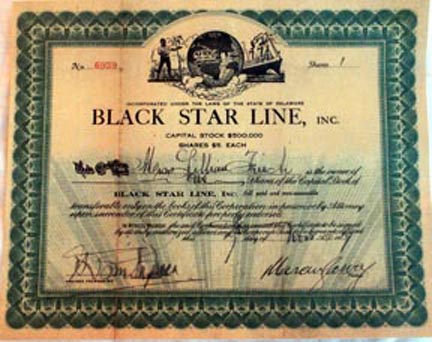

Black Star Line Stock Certificate

Garvey on board ship being deported |

Garvey faithful come to say goodby |

|

August 17, 1887 � June 10, 1940 Garvey is one of the most contradictory and enigmatic figures in American history. Garvey was a Jamaican political leader, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur and orator. Garvey was an adamant proponent of the Pan-Africanism and Black nationalism movements. To support his movements he founded the (UNIA-ACL). He also founded the Black Star Line which was part of the Back-to-Africa movement which promoted the return of the Black diaspora to their native continent. Prior to the 20th century some Black leaders such as Martin Delany, Edward W. Blyden, Henry H. Garnet, and Prince Hall. Advocated the involvement of the African diaspora in African affairs. Garvey was unique in advancing a Pan African philosophy that he hoped would inspire a global mass movement and economic empowerment with Africa as its center. Garvey would eventually inspire others such as the Nation of Islam to the Rastafari movement. Garvey�s intent was for those of African ancestry to reclaim Africa and for the European colonial powers to leave the continent. His essential ideals were stated in an editorial that he wrote in the �Negro World." He wrote �Our union must know no climes, boundary or nationality�to let us hold together under all climes and in every country. After leaving Jamaica in 1910 Garvey traveled through Central America and worked many jobs. Garvey was very impressed with Booker T. Washington, as he was with Martin Delany and Henry McNeal Turner. After corresponding with Washington he came to America on March 23, 1916 to give a lecture tour and to raise money to establish a school in Jamaica modeled after Washington�s Tuskegee Institute. Garvey visited a number of Black leaders. Garvey�s influence grew with Blacks all over the world from a cultural position and some important business ventures. He was a brilliant speaker and used his charismatic personality to raise funds for a number of ventures. These included:

The African Commercial League / African Factories Corporation Liberian Construction Liberty University, a training school in Virginia modeled after Tuskegee Institute Along the way Garvey developed many enemies. Most of these were not White, but Black. One of those was WEB Du Bois. Initially Du Bois was impressed with Garvey. He felt that the Black Star Line was original and promising. However as Garvey gained prominence his attitude changed as can be seen by some DuBois�s quotes: �Marcus Garvey is, without doubt the most dangerous enemy of the Negro race in America and in the world. He is either a lunatic or a traitor.� Garvey and Du Bois were opposite in personality and in method. Garvey wanted to keep the races separated while Du Bois was an integrationist. Du Bois feared that Garvey�s activities would undermine his influencing Blacks from his points of view. This rhetoric was not one-sided, Garvey also had negative words for Du Bois. Garvey thought that Du Bois was prejudiced against him because he was a Caribbean native with black skin. Du Bois once described Marcus Garvey as �a little, fat black man; ugly, but with intelligent eyes and a big head.� On the other hand Garvey described Du Bois as, �purely and simply a white man�s nigger� and �a little Dutch, a little French, a little Negro,a mulatto, a monstrosity.� This led to very hard feelings between Garvey and the NAACP, because Du Bois was one of its founders. Garvey accused Du Bois of paying conspirators to sabotage his Black Star Line to destroy his reputation. It didn�t help matters that Garvey had met with leaders in the Ku Klux Klan to gain their support for his back to Africa movement. Garvey recognized that the Klan had a great deal of influence in America. He set up a meeting with the KKK imperial giant Edward Young Clarke in 1922. In Garvey�s of words he said: �I regard the Klan, the Angle-Saxon clubs and White American societies, as far as the Negro is concerned, as better friends of the race than all other groups of hypocritical whites put together. I like honesty and fair play. You may call me a Klansman if you will, but, potentially, every white man is a Klansman, as far as the Negro in competition with whites socially, economically and politically is concerned, and there is no use lying.� Leo H. Healy publicly accused Garvey of being a member of the Ku Klux Klan in his testimony during Garvey�s mail fraud trial. After Garvey�s meeting with the Klan a number of African American leaders appealed to the U.S. Attorney General to have Garvey incarcerated. Among the many businesses that Garvey started the most noteable was the Black Star Line. It was not only his greatest achievement but it also led to his downfall. The Black Star Line was a shipping line incorporated by Garvey and managed by the UNIA. It was planned that the line would facilitate the transportation of goods and one day to African Americans throughout the African global economy. The line started in Delaware on June 23, 1919. It had a maximum capitalization of $500,000 Black Star Line stocks. These stock certificates were sold at UNIA conventions at five dollars each. The line surprised all of its critics when after being incorporated for only three months it purchased the first of four ships. This was the SS Yarmouth. The Yarmouth was an old World War One coal burner in poor condition when purchased by the Line. The inexperienced UNIA management team was duped by the seller. However it was reconditioned and preceded to sail for three years between the U.S. and the West Indies. It was the first ship with an all-Black crew and a Black captain. The purchases of three other ships followed. All of which were in poor condition. One was the SS Shadyside which sailed the Hudson. After only sailing one month it sank because of a leak. Another was a yacht once owned by the friend of Booker T. Washington, Henry H. Rodgers. An ill fate befell this ship also. It was the Kanawha but renamed the SS Antonio Maceo. It blew a boiler and a man was killed. Not only was the fleet an economic blight on Garvey but poor management and corrupt dealings by some UNIA management members were responsible for the downfall of him also. The company�s losses were estimated to be between 630,000 and 1.25 million dollars. The Black Star Line ceased its operation in February 1922. In spite of its many problems it was a major accomplishment for African Americans for the time. This, in spite of thievery by employees, engineers, and J. Edgar Hoover�s Bureau of Investigations�, FBI, acts of infiltration and sabotage. According to historian Winston James, one act of sabotage was done by an FBI agent by throwing foreign matter into the fuel supply, which damaged the engines. In November of 1919 under the direction of J. Edgar Hoover the BOI was summoned to investigate the activities of Garvey and the UNIA. This was in spite of the fact that nothing could be found to warrant such an investigation. In a memo from J. Edgar Hoover dated October 11, 1919 he stated: �Unfortunately, however, he [Garvey] has not as yet violated any federal law whereby he could be proceeded against on the grounds of being an undesirable alien, from the point of view of deportation.� Toward the end the BOI investigation, and under interesting circumstances, the BOI hired its first five African-American agents. They were Earl E. Titus, James Wormley Jones, Thomas Leon Jefferson, and James Edward Amos. Jones infiltrated the UNIA and based on his work this led to the arrest and trial of Garvey on mail fraud. Although first efforts by the BOI was to find grounds upon which to deport Garvey as �an undesirable alien mail fraud was introduced concerning the purchase of the Black Star Line. The prosecution used witnesses against Garvey and the UNIA who, after the trial, said that they had been coerced by BOI agents to lie in order to convict Garvey. Garvey and four members of the UNIA were put on trial and found guilty. However, only Garvey received jail time. Garvey stated later: When they wanted to get me they had a Jewish judge try me, and a Jewish prosecutor, I would have been freed but two Jews on the jury held out against me ten hours and succeeded in convicting me, whereupon the Jewish judge gave me the maximum penalty. It was Garvey�s position that the Jews hated him because of his relationship with the Klan. Garvey spent three months in the Tombs Jail while waiting approval of bail. While out on bail he continued to maintain his innocence, travel, speak and organize the UNIA. After numerous attempts at appeal were unsuccessful he was taken into custody and began serving his sentence at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. Two days after entering prison he wrote his well-known �First Message to the Negroes of the World From Atlanta Prison. His famous proclamation:

For, with God�s grace, I shall come and bring with me countless millions of Of black slaves who have died in America and the West Indies and the Millions in Africa to aid you in the fight for Liberty, Freedom and Life.�

On June 10, 1940, Garvey died after two strokes reportedly after reading a mistaken posted and negative obituary of himself in the Chicago Defender. The obituary stated that Garvey died broke, alone and unpopular. All of which Garvey denied.

The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey. Edited by Amy Jacques Garvey. 412 pages. Majority Press; Centennial edition, 1 November 1986. ISBN 0-912469-24-2. Avery edition. ISBN 0-405-01873-8. Message to the People: The Course of African Philosophy by Marcus Garvey. Edited by Tony Martin. Foreword by Hon. Charles L. James, president- general, Universal Negro Improvement Association. 212 pages. Majority Press, 1 March 1986. ISBN 0-912469-19-6. The Poetical Works of Marcus Garvey. Compiled and edited by Tony Martin. 123 pages. Majority Press, 1 June 1983. ISBN 0-912469-02-1. Hill, Robert A., editor. The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers. Vols. I-VII, IX. University of California Press, ca. 1983- (ongoing). 1146 pages. University of California Press, 1 May 1991. ISBN 0-520-07208-1. Hill, Robert A., editor. The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers: Africa for the Africans 1921-1922. 740 pages. University of California Press, 1 February 1996. ISBN 0-520-20211-2.

Burkett, Randall K. Garveyism as a Religious Movement: The Institutionalization of a Black Civil Religion. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press and American Theological Library Association, 1978. Campbell, Horace. Rasta and Resistance: From Marcus Garvey to Walter Rodney. Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 1987. Clarke, John Henrik, editor. Marcus Garvey and the Vision of Africa. With assistance from Amy Jacques Garvey. New York: Vintage Books, 1974. Cronon, Edmund David. Black Moses: The Story of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1955, reprinted 1969 and 2007. Hill, Robert A., editor. Marcus Garvey, Life and Lessons: A Centennial Companion to the Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987. Hill, Robert A. The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers. Vols. I�VII, IX. University of California Press, ca. 1983� (ongoing). James, Winston. Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia: Caribbean Radicalism in Early Twentieth-Century America. London: Verso, 1998. Kornweibel Jr., Theodore. Seeing Red: Federal Campaigns Against Black Militancy 1919-1925. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1998 . Lemelle, Sidney, and Robin D. G. Kelley. Imagining Home: Class, Culture, and Nationalism in the African Diaspora. London: Verso, 1994 . |