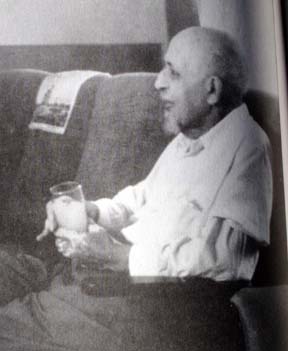

The Last Photo Of W.E.B. Du Bois age 93

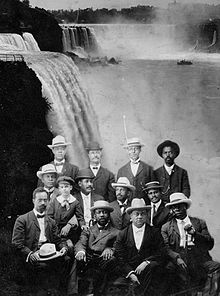

First Niagra Meeting class |

Women of Niagara |

Writer Zora Hurston

|

The Great Migration

|

The Burning of William Brown

William Edward Burghardt �W.E. B. Du Bois"February 23, 1868 �August 27, 1963-

BACKGROUNDDu Bois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts on February 23, 1868 to mixed parents. His former generations had been well established in Great Barrington and owned land in the state. There were few Blacks in the town and Du Bois grew up with White kids as playmates. He experienced no racism in his formative years. He was a good student and was encouraged by his teachers to pursue his intellectual pursuits. As he grew older he became aware of the racism practiced against other Blacks. His academic skills led him to believe that he could use his knowledge to empower African Americans. His parents had little money so friends and church members funded his tuition. He graduated from Harvard with honors. He was the first African American to earn a doctorate. He became a professor of history, sociology and economics at Atlanta University. He later was a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He rose to prominence as the leader of the Niagara Movement. This was a group of Black activists who would work for equal rights for Blacks. He and his supporters were in opposition to Booker T. Washington and his policy to advance the race. Du Bois and his associates referred to Washington�s policy as the �Atlanta Compromise." This was an agreement between Booker T. Washington and the White power structure in the South. The agreement provided that Southern Blacks would work and acquiesce on any political power. While Southern Whites guarantee that Blacks would receive a basic education, economic opportunities plus have protection under the law. This was contrary to the position taken by Du Bois. Du Bois demanded full civil rights and increased political power for Black Americans. He thought that this would be brought about by Blacks with superior intellect. He referred to this group as the �talented tenth." Although he was never exposed to racism as a youngster he was violently opposed to it. He was firmly opposed to Jim Crow laws, lynching and the disenfranchising of African-Americans. He was also against imperialism and colonialism. Du Bois was a proponent of Pan-Africanism and helped in the organization of a number of Pan-African Congresses. It was his desire to have all of Europe out of Africa. Du Bois coined two phrase that came to be popular, �the submerged tenth� and the "Talented �tenth.� He used the term �Talented tenth� to describe a society�s elite class. It was his position that the elite class of a society, Black and White, was that portion of society responsible for the progress of its people. His writings were dismissive of the characterizations of the �Submerged tenth,� by other writers when they described these as unreliable and lazy people. He attributed many social problems to the legacy of slavery.

THE ATLANTA COMPROMISEAt the start of the 20th century Du Bois had advanced himself to be the number two spokesman for African-Americans. He was second only to Booker T. Washington. Washington was the creator of what became known as the Atlanta Compromise. This term was created by Du Bois and was a direct criticism against Washington. This was an unwritten agreement between Southern White leaders, who had gained all political power in the vacuum left by the failed policy of �Reconstruction.� The agreement provided for Blacks to submit to segregation, discrimination, and the lack of voting rights and that Southern Whites would permit Black�s to receive a basic education, some economic opportunities and justice within the legal system. Du Bois and other northern Blacks who were educated were diametrically opposed to this deal. They felt that Black Americans should fight for equality instead of submitting to the segregation and discrimination of Washington�s compromise. The lynching of Sam Hose, which occurred near Atlanta in 1899 infuriated Du Bois. Hose was tortured, burned and hung by a mob of two thousand. Du Bois went to Atlanta to discuss the lynching with a newspaper editor. While he was in Atlanta he found the burned knuckles of Hose in a storefront display. The sight of it inspired Du Bois to resolve to act. Act not only on telling the truth about conditions in the South but to act on the truth. In 1901 Du Bois wrote a critical review on Washington�s book �Up From Slavery. He later expanded of it and published it to reach a greater audience. It was named �Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others.� His book, �The Souls of Black Folk," revealed the great contrast between Washington and himself. Washington thought that Blacks should be schooled in industrial education, agricultural and mechanical skills while Du Bois felt that Blacks should also receive a liberal arts education. He felt that training in liberal arts was required to develop leaders. A joke of the day from supporters of the Du Bois to counter the argument that a college degree from Tuskegee would open many doors. It said the only doors that a degree from Tuskegee would teach you to open was to open the car door for the White man and the door to the house for the White man, etc.

THE NIAGARA MOVEMENTIn 1905 Du Bois and several other Black civil righters met near Niagara Falls, Canada. This group of men wrote a declaration of principles opposing the Atlanta Compromise and incorporated themselves as the Niagara Movement. The Niagara group wanted to publicize their ideals to other Black Americans, however most of the Black periodicals were owned by publishers to sympathetic to Washington. So Du Bois bought a printing press and published �Moon Illustrated Weekly" in December 1905. This was the first Black illustrated weekly. Du Bois used the weekly to attack Washington�s position. However, the magazine only lasted eight months. Undaunted, Du Bois founded and edited another paper: "The Horizon: A Journal of the Color Line.� The weekly debuted in 1907. The group held a second conference in August 1906 to celebrate the anniversary of John Brown�s birth. The meeting took place where Brown was defeated, Harper�s Ferry, West Virginia. A leading member of the group, Bishop Reverdy Cassius Ransom spoke and addressed the fact that Washington�s goal was to provide employment to Blacks. He said: �Today, two classes of Negroes,�are standing at the parting of the ways. The one counsels patient submission to our present humiliations and degradations�The other class believe that it should not submit to being humiliated, degraded, and remanded to an inferior place�it does not believe in bartering its manhood for the sake of gain. RACIAL VIOLENCEIn the fall of 1906 two incidents shocked Black America and propelled Du Bois�s struggle for civil right over that of Booker T. Washington�s accommodation views. President Teddy Roosevelt dishonorably discharged 167 Black soldiers because they were accused of crimes as a result of the �Brownsville Affair.� Many of the discharged soldiers had served for 20 years and were close to retirement. They being discharged dishonorably meant that they would not be receiving their pensions. The Brownsville Affair was a racial incident that came from tensions between Black soldiers and White citizens in Brownsville, Texas. A White bartender was killed and a policeman was wounded by a gunshot. White civilians accused members of the 25th Infantry Regiment, a Buffalo Soldier unit stationed at nearby Fort Brown. They could not have been involved because they had been in their barracks all night. They were framed when evidence was planted against them. An investigation, 64 years later in 1970, exonerated the discharged Black troops and the government pardoned them and restored there records showing them as being honorably discharged. However their was no retroactive compensation. In September riots broke out in Atlanta brought on false allegations that Black men were assaulting White women. This, coupled by a job shortage and more erroneous claims led to employers playing Black and White workers against each other. Ten thousand Whites rampaged the streets of Atlanta beating every Black person that they came upon. Twenty-five Blacks were murdered in this melee. Following this event Du Bois urged Blacks to quit the party of Lincoln, the Republican Party. Blacks had been supportive of the Republican Party since the time of Abraham Lincoln. They urged the des-union because Presidents Roosevelt and William Howard Taft did not support Blacks. Du Bois wrote of the affair in an essay, �A Litany at Atlanta." This essay asserted that the Atlanta Compromise was a failure because despite Blacks upholding their end of the bargain, African-Americans did not receive the legal justice they were promised. The White plantations owners who originally agreed to the compromise had been replaced by other types who were eager to pit Blacks and Whites against each other. These two events marked the downfall of Washington�s Atlanta Compromise and ascended the vision of Du Bois on equal rights.

THE CRISIS MAGAZINEThrough the Crisis Magazine Du Bois was able to highlight many injustices against Blacks. Not only did Du Dois have issues with Washington he also had problems with the Women�s Right-To-Vote movement. He did so because leaders of the movement refused to support his fight against racial injustice. He was not alone in this matter. Women such as Sojourner Truth and Ida Wells were supporters but were disillusioned by that organization when they would not support the fight against racial injustice. Because President Taft did not deal with wide spread lynching Du Bois, using the Crisis Magazine, endorsed Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson in the 1912 presidential race in exchange for Wilson�s promise to support Black causes.

BLACKS BEING TRAINED AS OFFICERSAs the country was preparing to enter WWI a colleague, Du Bois, and fellow member in the NAACP, Joel Spingarn, established a camp to train Black Americans to serve as officers in the United States military. Two of many problems emerged. Most Whites did not believe that Blacks were qualified to be officers, and others felt that this was a White man�s war. Du Bois and the NAACP supported the camp. However, they were disappointed when the Army forcibly retired one of its few Black officers Colonel Charles Young. They did so under the pretense that Young was of bad health. It was said that his blood pressure was too high. To prove to the Army that he was fit Young mounted a horse and road 500 miles from Wilberforce, Ohio to Washington, DC. However this did not change the minds of the military so he filed a petition to the Secretary of War to be reinstated. He was reinstated but by the time the reinstatement took effect WWI was almost over. He was assigned to a remote location, Camp Grant, Ill and then sent to Liberia. He was doing duty in Logos when and where he died. The Army agreed to create 1,000 officer positions for Blacks but insisted that 250 come from the ranks of enlisted Blacks who were conditioned to taking orders from Whites. They did not want the independent-minded Blacks that would come out of the Spingarn camp. The Houston Riot in 1917 was a major setback for Blacks who wanted to be accepted as officers. The riot began when Houston police arrested and beat two Black soldiers. In response to this over 100 Black soldiers took to the streets of Houston and as a result 16 Whites were killed. During the military court martial 19 of the soldiers were hung and 67 others were sent to prison. In spite of this Du Bois and his followers were successful in their efforts to get the Army to accept Black officers who were trained at Spingarn�s camp. Following the East St Louis Riot in 1917 Du Bois traveled to St Louis to cover the riot for his magazine. Up to 250 Blacks were murdered by Whites primarily due to resentment caused by St Louis business hiring Blacks to replace striking White workers. Du Bois wrote about this in the Crisis magazine. Noted historian David Levering Lewis, back-to-back Pulitzer Prize winner on the autobiography of Du Bois, said that Du Bois distorted some of the facts in order to increase circulation of his magazine.

WWIFor the most part during the war Black soldiers were assigned menial labor tasks such as stevedores and laborers. However some units saw combat such as the highly decorated 92nd Division, the (Buffalo soldiers). Du Bois discovered that the Army discouraged Blacks from joining the army and discredited the accomplishments of Black soldiers. Following his return from Europe Du Bois was dedicated more than ever to gain equal rights for African Americans. The returning Black soldiers were equipped with a new sense of power and of �self.� They were in possession of a new attitude. They were referred to as the �New Negro.� Du Bois wrote in the editorial �Returning Soldiers�: But by the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if, now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.� This new attitude caused friction in the northern cities as both the Black and White labor forces competed for jobs. But the Black worker gave as much as he took in physical exchanges. This resulted in what has been referred to as the �Red Summer of 1919." This was a series of race riots across the country which resulted in over 300 Black Americans being killed in over 30 cities. Du Bois documented the atrocities in the Crisis. In the December publication there was a gruesome picture of the lynching and burning of William Brown. See photo. . HARLEM RENAISSANCEThe Harlem Renaissance was a period of cultural display and connected with the �New Negro� from 1919 to 1934. The Harlem Renaissance was dominated by Du Bois and his close associate Alain Leroy Locke. Locke was an American writer, philosopher, educator and patron of the arts. He was a man of wealth and first Black Rhodes Scholar from Harvard. He is referred to as the Dean of the Harlem Renaissance. The purpose of the Renaissance from the perspective of Locke and Du Bois was to propel the Negro forward through the art of the race. They recruited Black artists from all of the country to participate. They were not interested in showcasing the art of Africa, especially Du Bois. They wanted Black artist that displayed the root of the White influence. Du Bois wanted Black artists to use their art to promote Black causes. He said: �I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda.� The Renaissance was not only about art, Marcus Garvey played a major roll in Harlem during that time. PEACE ACTIVISMDu Bois was a peace activist for the whole of his life. He had always been an anti-war activist, but his efforts expanded during WWII. These efforts got him in trouble in with the United States government and led to his having to surrender his passport. He spoke at the Scientific and Cultural Conference for World Peace in New York. �I tell you, people of America, the dark world is on the move! It wants and will have Freedom, Autonomy and Equality. It will not be diverted in these fundamental rights by dialectical splitting of political hairs�Whites may, if they will, arm themselves for suicide. But the vast majority of the world�s peoples will march on over them to freedom.� In 1949 he spoke at the World Congress of the Partisans of Peace in Paris. He said to the crowd: Leading the new colonial imperialism comes from my own native land built by my father�s toil and blood, the United States. The United States is a great nation; rich by grace of God and prosperous by the hard work of its humblest citizens�armed with power we are leading the world to hell in a new colonialism with the same old human slavery which once ruined us; and to a third World War which will ruin the world.� He affiliated himself with a leftist organization, the National Council of Arts, Sciences and Professions. He traveled to Moscow as its representative to speak at the All-Soviet Peace Conference in the latter part of 1949. To keep him from going the United States government confiscated his passport and withheld it for eight years. At the age of 82 in 1950 Du Bois ran for the UA Senate seat from New York on the American Labor Party ticked and received 4%, 200,000 votes. He continued to believe and preach that capitalism was the primary force behind the subjugation of colored people around the world. Although he saw the faults of the Soviet Union he continued to uphold communism as a possible solution to the worlds racial problems. According to David Levering Lewis �Du Bois did not endorse communism for its own sake, but did so because �the enemies of his enemies were his friends.� The United States government prevented Du Bois from attending the 1955 Bandung conference in Indonesia. It was a lifelong dream of his to attend such an event. Twenty nine countries from Asia and Africa representing most of the world's colored people. It was a celebration of their independence. These nations began to flex their muscles as non-aligned countries during the cold war. He was able to regain his passport and traveled around the world. His highlight was visiting Russia and China. In both these countries he was warmly welcomed. He was shown the best aspects of communism. He welcomed the show but at the same time he knew of the faults of both countries. At this time he was 90 years old.

DEATH IN AFRICAHe was invited by Ghana to Africa�s celebration of independence in 1957, however he was unable to attend because once again the United States government had taken his passport. In 1960 he had regained his passport and celebrated the creation of the Republic of Ghana. While in Ghana in 1960 Du Bois brought up the subject of a new encyclopedia of the African diaspora, the Encyclopedia Africana. His words were warmly received and in 1961 he was notified by Ghana that they had appropriated funds to support the encyclopedia project. They invited Du Bois to come to Ghana to manage the project. In 1961 he, at age 93, and his wife went to Ghana to live and take on the project. In 1963 the U.S. refused to renew his passport so he made emblematic gesture of becoming a citizen of Ghana. His health declined during the two years that he was in Ghana and he died on August 27, 1963. He was buried in Accra near his home, which is now the Du Bois Memorial Center. The day following his death at the March on Washington speaker Roy Wilkins asked the hundreds of thousands of marchers to honor him with a moment of silence. |